Review: The Power of Habit

The Power of Habit by Charles Duhigg is the reason that I just turned on a Pomodoro timer to write this review. He doesn’t ever mention it in his book (I think I Mandela effect-ed myself into believing that was the case), I’d heard of a Pomodoro timer before, but largely dismissed it as being silly. This book takes you on a journey through the power of human habit that is so illuminating and powerful that it convinced me to take on new strategies to combat my worst habit: distractibility. So sit down and shut up reader, because for the remaining ~18 minutes1, I’m going to be so fucking focused on reviewing this book you’re not going to believe it.

Duhigg starts small in scope, showing us the habits of individual smokers, over-eaters, alcoholics who are now regularly jogging, eating salads, and excelling in their careers. The first three before descriptions don’t quite match with the after ones, and that’s part of the point. One of the first revelations in the book is that changing one bad habit often cascades into other parts of your life. Duhigg first focuses on Lisa, a smoker who was suffering through a rough divorce, and makes a rash trip to Cairo, even more rashly vowing that she would return in a year to trek through an Egyptian desert. For that to be possible, she decided she would need to give up smoking.

[…] to the scientists at the laboratory, the details of her trek weren’t relevant. Because for reasons they were just beginning to understand, that one small shift in Lisa’s perception that day in Cairo—the conviction that she had to give up smoking to accomplish her goal—had touched off a series of changes that would ultimately radiate out to every part of her life. Over the next six months, she would replace smoking with jogging, and that, in turn, changed how she ate, worked, slept, saved money, scheduled her workdays, planned for the future, and so on. […]

It wasn’t the trip to Cairo that had caused the shift, scientists were convinced, or the divorce or desert trek. It was that Lisa had focused on changing just one habit—smoking—at first. […] By focusing on one pattern—what is known as a “keystone habit”—Lisa had taught herself how to reprogram the other routines in her life, as well.

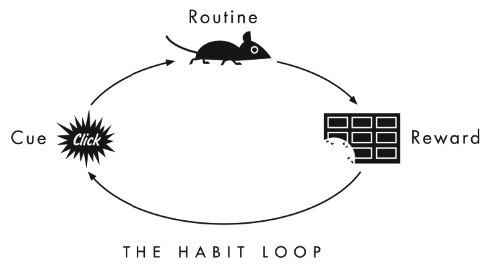

Keystone habits pop up a lot in this book, I’d call them, and “The Habit Loop”, the main characters, and probably what you should focus on if you’re hoping to use this book to change your own habits2.

Duhigg quickly establishes this loop and its power through a few studies (including the curious case of Eugene Pauly, who suffered severe brain damage, leaving only his habitual mind) and applies it to each story in the book. The book is mostly stories and anecdotes from the subjects of these academic studies on habits. The structure is nicely done to stop the book from being too dry, using individual stories is effective for keeping my attention and getting your point across in concrete ways. But you can quit it with the bullshit cliffhangers all over the place. At least once a chapter Duhigg builds the story up to a point of “and you’ll never guess what happens next” then do a line break and jump back in the storyline, or sometimes to a totally different one. It’s not a large complaint, but it baffled me every time that this man is telling me to tune in next week so I can catch the thrilling conclusion to how Starbucks works.

The book is split into 3 parts, growing in scope as Duhigg explores habits in individuals, companies, and finally societies. This is where the more “academic” aspects of the book come in, and where I think it gets its most interesting, but also less useful for a distracted engineer to immediately incorporate in his life.

Part 1: Habits of Individuals

Habits are hard to manufacture, that’s basically the entirety of LA Fitness’s business model. Get you to buy a membership intending to build this new, healthy habit, then make it impossible to cancel the thing when you inevitably don’t actually go with a combination of shame and bureaucratic bullshittery. It’s tricky because habits are built in pursuit of a reward, and if you don’t find an obvious reward at the end of that treadmill, it’s hard to keep up, and if for whatever reason your brain isn’t coded to accept that exercise endorphin rush as a good thing, then you’ve got to employ other strategies. For this reason only one chapter is spent on creating new habits, while most others are focused on changing existing ones.

Habits aren’t destiny. […] habits can be ignored, changed, or replaced. But the reason the discovery of the habit loop is so important is that it reveals a basic truth: When a habit emerges, the brain stops fully participating in decision making. It stops working so hard, or diverts focus to other tasks. So unless you deliberately fight a habit—unless you find new routines—the pattern will unfold automatically.

However, simply understanding how habits work—learning the structure of the habit loop—makes them easier to control. Once you break a habit into its components, you can fiddle with the gears.

The power of habit is that our brains run a program in the background to save its energy when certain conditions are met. And if you can modify the program, you can train your brain in some useful ways. As a programmer this is a fascinating revelation, that my brain is running cron jobs all the time, and with a little work I can tweak the commands being run. But I can never delete them. This seems accepted a priori in the book, that habits are near impossible to fully delete. Duhigg writes, if you’ve Pavlov-ed3 yourself into drinking a beer every time the football game is on, you’ll find it incredibly difficult to stop and just drink nothing. Your cue (football game), routine (get a beer), and reward (taste and sweet oblivion) have been indelibly established. You’ll have much better luck tweaking the routine part4 of that habit loop, so reaching for a seltzer water or non-alcoholic beer instead will greatly increase your chances of changing your routine. The difficult part here is stopping your brain from shutting off. You have to be vigilant to recognize the habit and each part of the loop that is in play. When you’ve done that, you then have to stop your brain from going with its usual behavior and shift it to the new one.

I get the sense that Duhigg isn’t a big drinker, smoker, or recreational drug user of any kind. The book has little lip service paid to the unending difficulties of uprooting bad habits like addictive drugs, lip service that most current and former drug aficionados cannot resist opining on. Although he brings up examples of people quitting smoking and drinking utilizing these habit-modification techniques (there’s quite a few mentions of Alcoholics Anonymous), there’s little said about chemical addiction. It seems to me that chemical addiction would be something like habit formation in overdrive, or it maybe reinforces the reward part of the loop so deeply that nothing else can emulate it. Though he does acknowledge this is all easier said than done.

It is important to note that though the process of habit change is easily described, it does not necessarily follow that it is easily accomplished. It is facile to imply that smoking, alcoholism, overeating, or other ingrained patterns can be upended without real effort. Genuine change requires work and self-understanding of the cravings driving behaviors. Changing any habit requires determination. No one will quit smoking cigarettes simply because they sketch a habit loop.

Part 2: Habits of Companies

Keystone habits pop up occasionally when Duhigg talks about individuals, but they really come into play for corporate habits. I think because a corporation is a much bigger beast than an individual, so if you’re looking to change any habits, there’s mountains more friction in your way, so picking a single habit that can have far-reaching consequences if far preferable. He opens this section by exploring the newly appointed CEO of the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa), Paul O’Neill. O’Neill sought to turn around the flailing company by doing something no 1980s business man could dream of: make the workplace safer.

O’Neill believed that some habits have the power to start a chain reaction, changing other habits as they move through an organization. Some habits, in other words, matter more than others in remaking businesses and lives. These are “keystone habits,” and they can influence how people work, eat, play, live, spend, and communicate. Keystone habits start a process that, over time, transforms everything.

O’Neill identified factory safety as the keystone habit to change, and he really fucking cared about it. It wasn’t some bullshit pandering that bigwigs said to quiet the rabble, he bought better machines, implemented new standards, and fired an effective executive when that exec was slow to report an incident in accordance with O’Neill’s new standards. Before O’Neill, the company was getting wrecked by competitors, and everyone assumed this focus on safety would slow down Alcoa even more. His investors balked in classic 1980s businessman fashion: “Profit is driven by children’s faces covered in coal dust! Asbestos filled machines with every surface sharpened to a razor’s edge! If I so much as hear about an emergency shutoff I’m going to fill the room with chainsaws!”

But O’Neill kept at it, the safety records meaningfully improved, as did the rest of the company. It turns out safety was a keystone habit and improving it triggered a slew of other improvements. The newer machines were safer, they also jammed less and made better products. Workers trusted management more, management trusted workers more, and overall productivity soared.

If you focus on changing or cultivating keystone habits, you can cause widespread shifts. However, identifying keystone habits is tricky. To find them, you have to know where to look. Detecting keystone habits means searching out certain characteristics. Keystone habits offer what is known within academic literature as “small wins.” They help other habits to flourish by creating new structures, and they establish cultures where change becomes contagious.

The “if you know where to look” part is the rub here, as not much direction is given in that aspect. Though just observationally through some of the book’s examples, the answer tends to be something innocuous that also touches many aspects of the whole process5. If you can change that, so much more can change as well. For individuals, a common one is exercise, but I’m unsure if companies share any common ones to focus on.

The other big example Duhigg uses isn’t necessarily the habit of a company, but rather how companies have independently discovered the powers of habit, and effectively exploit them to a creepy degree. He details the story of Target’s data scientists who were able to spot when people were pregnant, sometimes even before the mothers themselves knew. Target would track purchase histories, and found out that newly-pregnant women bought at each stage of pregnancy, and would send them coupons for those items. New mothers found this creepy as shit6, so Target learned to get sneaky with it. You’d get a coupon booklet for a bunch of stuff, plus a couple of totally-not-targeted stroller and diaper discounts.

Part 3: Habits of Societies

This section has me conflicted. I simultaneously believe Duhigg is reaching too far, but maybe has a point. The big focus is the Montgomery bus boycott that Rosa Parks kicked off, and launched MLK. Duhigg’s argument is that anti-black discrimination in Montgomery was habitual. The exchange between Rosa Parks and the cop who arrested her bolsters this (and is also pretty gangster shit from Rosa Parks).

“If you don’t stand up,” [the bus driver] said, “I’m going to call the police and have you arrested.”

“You may do that,” Parks said.

The driver left and found two policemen.

“Why don’t you stand up?” one of them asked Parks after they boarded.

“Why do you push us around?” she said

“I don’t know,” the officer answered. “But the law is the law and you’re under arrest.”

“You may do that” is a fantastic, movie-worthy line, and so is the officer saying “I don’t know”. It perfectly encapsulates Duhigg’s point that this discrimination had fallen into the habit loop where white people didn’t even think about their behavior, their brains went on auto-pilot and discriminated because it was the easy thing to do, and black people withstood the abuse because they had adopted a habit to do so.

A lot has been said about why specifically Parks was the one to spark this revolution, she wasn’t the first black person to refuse to give up her seat on the bus, but she was a beloved community figure who was involved with a lot of tight-knit communities in the area, so she was easy to rally around. There were a lot of social science phenomena going on during the Montgomery bus boycotts, but I’m not fully convinced that habits were a part of it. Duhigg asserts that habits of friendship and social interaction dictate a lot of what happened in Montgomery.

Movements don’t emerge because everyone suddenly decides to face the same direction at once. They rely on social patterns that begin as the habits of friendship, grow through the habits of communities, and are sustained by new habits that change participants’ sense of self.

I still think Duhigg is doing some round-peg-square-hole work here. Habits are powerful forces in our lives, as he’s proved in previous chapters, but was it adherence to habits that kept protestors in the streets? Or was it the power of the ideals they were fighting for, and the extraordinarily charismatic leader in MLK that kept them going? I’d wager the latter as a more powerful force in compelling behavior on this sort of scale.

The Freewill Thing

Habits are a powerful and fundamental force of the human mind. We quite literally stop thinking and assessing our actions for moments of time to get our reward. So are we a slave to the habits? Are we simply collections of cron jobs running all day? And are we responsible for their consequences?

So much of my own time has been spent on pushing this freewill thought around in circles I kind of checked out for this section. I think freewill is the ultimate nerd-snipe for the philosophically minded, and until we can get some sort of smoking gun, we’re going nowhere. And habits are not that smoking gun. Duhigg clearly shows that with a little work, we can modify and interrupt habits. Maybe you lose autonomy for a little bit, but you can recognize and fight it with the proper willpower, strategy, and assistance.

Key Takeaways

- The habit loop is powerful, and shuts your brain off to save energy. Knowing this enables you to recognize the loop and modify it, which is generally the best way to approach things as habits are hard to manufacture, but relatively easy to change.

- Habits are near impossible to completely delete without some surgery or copious amounts of booze.

- Recognizing the habit is the first step, then the hard work of actually changing it begins.

- How to Modify the Habit: nail down the loop and you can change it. The loop components can be hard to spot.

- Identify the routine: figure out what habits you have

- Experiment with rewards: figure out what exactly the reward is, try new ones, see if you’re satisfied

- Isolate the cue: we’re bombarded with info and events, you need the exact thing that triggers your habit

- Have a plan: devise a specific plan that modifies the habit and execute it dutifully

This took far more time and timer session to finish than I anticipated. I had a draft where I included whenever I finished a session, but discarded that bit as it added little more than clutter. Albeit it’s an effective tool, enough that I already resisted trying to build my own program to do it, and bought my lifetime subscription to Pomofocus. ↩︎

As I imagine 99% of people who read this book are. ↩︎

Pavlov is not mentioned in this book at all. Not a single reference. I figure his work is probably wildly out of date at this point, and I can imagine anyone who loves dogs would probably not want to acknowledge his existence, but still, seems like an odd exclusion. ↩︎

I guess you could also eliminate the cue in this case, just never watch football. But that’s probably a non-starter for most. ↩︎

Side rant: I think focusing on eliminating automated test flakes would be a great candidate for this in a software company. Flakes are often frustrating, but accepted matter-of-fact and people just re-run the test. I think prioritizing eliminating flakey tests can bring a massive amount of organizational focus to bear on overall product quality. Less bugs and crashes, more focus on building maintainable and testable code, and less likelihood to ship broken shit. ↩︎

This is maybe showing the age of the book, but this felt very much like Duhigg was trying to shock me with the revelation that “corporations track your behavior!”, and I could feel his mood fall as I told him “ya, no shit they do”. I was also hoping for more deep dive on exactly the math/programming that went into Target’s system at the time, but I left understandably disappointed. ↩︎